Städtische Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau, the municipal arts & crafts school in the city of Breslau.

The movement to establish state-funded vocational arts schools in Germany gained traction in the mid nineteenth century with the advent of international expositions and under the influence of British efforts to foster applied art. Many German cities, mostly in the west, founded their own arts and crafts schools. In the large eastern areas of the country, only a handful were initiated, with provincial capital Breslau home to two of them, the Staatliche Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe and the Städtische Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule.

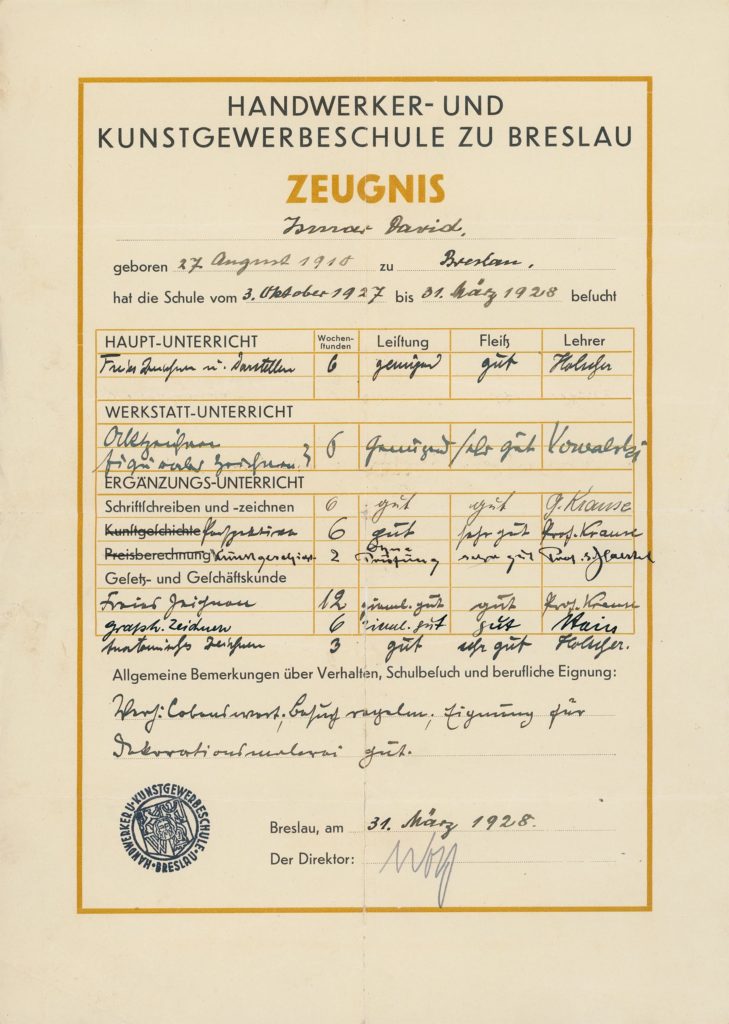

Ismar David attended the latter, the Municipal Arts and Crafts School of Breslau from the fall of 1927 through the spring of 1928, at the end of his apprenticeship and before he left his hometown for Berlin. The school was still struggling to emerge from the massive trauma inflicted by the aftermath of the First World War and disastrous hyperinflation. Long time director and professor Richard Heyer had retired in 1925 after twenty-five years service and the relatively new administration faced dilapidated and woefully inadequate accommodations for just about everything. (In 1929, the student body would still derisively call their Mardi Gras festivities, “Fest der Hinterhäusler,” which might be roughly translated to Slum Dwellers Celebration.”)1 Städtische Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau: Bericht 1926, 1927, 1928 der Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau, p. 8 Under the new director, architect Gustav Wolf, the school developed an extensive renovation plan that included support for a needy student population. In further recognition of the economic austerity of the era, the ethos of the school became “to still make necessities enjoyable, but to net clear effects with low expenditure of power and materials. … Making expensive things for the refined tastes of a small circle of connoisseurs isn’t paramount. Rather, we try to make useful things that most people need in their daily lives.”2 Städtische Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau: Bericht 1926, 1927, 1928 der Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau, p. 8

As its name implies the school received significant support from city authorities, with Silesian professional organizations contributing financially as well as administratively. This leadership saw the institution’s role as defending the cultural integrity of geographically isolated Silesia against absorption by a greater Germany and promoting Silesian arts and crafts, while offering the best possible training for the school’s mostly Silesian student body. Work experience was a general prerequisite for students, and the faculty were all active professionals in their respective fields. The multi-disciplinary institution vigorously cultivated cooperation among the various disciplines it offered: interior construction; applied sculpture, painting and graphics; metal work; glass decoration; porcelain painting; ceramics; book arts; tailoring, dressmaking and theater set construction; with each department having its own workshop or extensive series of workshops. (The book arts department alone had workshops in lithography, photochemical plate-making, hand and mechanical typesetting, letterpress and copperplate printing and bookbinding.)

All of Ismar David’s classes, however, came under the heading of general instruction. According to his certificate-cum-report card, Ismar David attended classes for exactly 6 months, with a total of 47 hours of classes per week—which accords with the normal schedule for a full-time attendee in a crafts school in those days (48 hours per week).3 Städtische Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau: Bericht 1926, 1927, 1928 der Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Breslau, p. 4 His choice of classes reflected his need to remediate his drawing skills: freehand drawing and representation (Hermann Holscher), nude model/figurative drawing (Ludwig Peter Kowalski), Freehand drawing (Georg Krause), drawing for commercial graphics (Gerhard Stein), anatomic drawing (Holscher), calligraphy and letter drawing (Krause). He had 2 hours a week of art history (Siegfried Haertel) and 6 per week calculating charges (Krause) as well. His teachers all deemed his work “sufficient” to “good” and his conduct “praiseworthy.” They affirmed his suitability for decorative painting. He was ready for his next step, the Municipal Arts and Crafts School Charlottenburg in Berlin.

| MAIN INSTRUCTION | Week-hours | Grade | Effort | Teacher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free drawing and representation | 6 | sufficient | good | Holscher |

| STUDIO INSTRUCTION | ||||

| Nude model Figurative drawing | 6 | sufficient | Very good | Kowalski |

| SUPPLEMENTARY INSTRUCTION | ||||

| Calligraphy and letter drawing | 6 | good | good | G. Krause |

| Calculating charges | 6 | good | Very good | Prof. Krause |

| Art history | 2 | Without exam | Very good | Prof. Haertel |

| Law and business administration | ||||

| Free drawing | 12 | Suffiently good | good | Prof. Krause |

| Graphic drawing | 6 | Rather good | good | Stein |

| Anatomic drawing | 3 | good | Very good | Holscher |

General remarks about conduct, attendance and professional suitability:

Conduct: commendable, regular attendance; suitability for decorative painting: good