Emotional expression and simplicity, key principles of Viennese sculptor and pedagogue Eugen Steinhof’s philosophy, characterize Moshe Ziffer’s early work. Steinhof encouraged his students to ignore small details to concentrate on the greater play of light on form.1Ballas, Gila, Moshe Ziffer The Man and the Artist, Research and Publications Archive, The David and Yolanda Katz Faculty of the Arts, Tel Aviv University. His student Moshe Ziffer’s many female nude studies, often compared to Maillol’s, eschew academic anatomical detail in favor of unfussy form and line. His sculpture, The Pioneer, for the Palestine Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair demonstrates this as well. These and smaller public works, including the gravestone for Chaim Bialik (in collaboration with the painter Moshe Mokdi in 1935), the monument for the controversial re-interment of Ber Borochov and his wife in Kinneret Cemetery (in collaboration with Aryeh Sharon)2The Unveiling Ceremony of Borochov’s Grave…, Mishmar-The Guard, November 9, 1964. Tel Aviv, p. 7. and the Weizmann gravestone were comprised of bold forms, without ornamentation, except, in some cases, a figurative image of some kind.

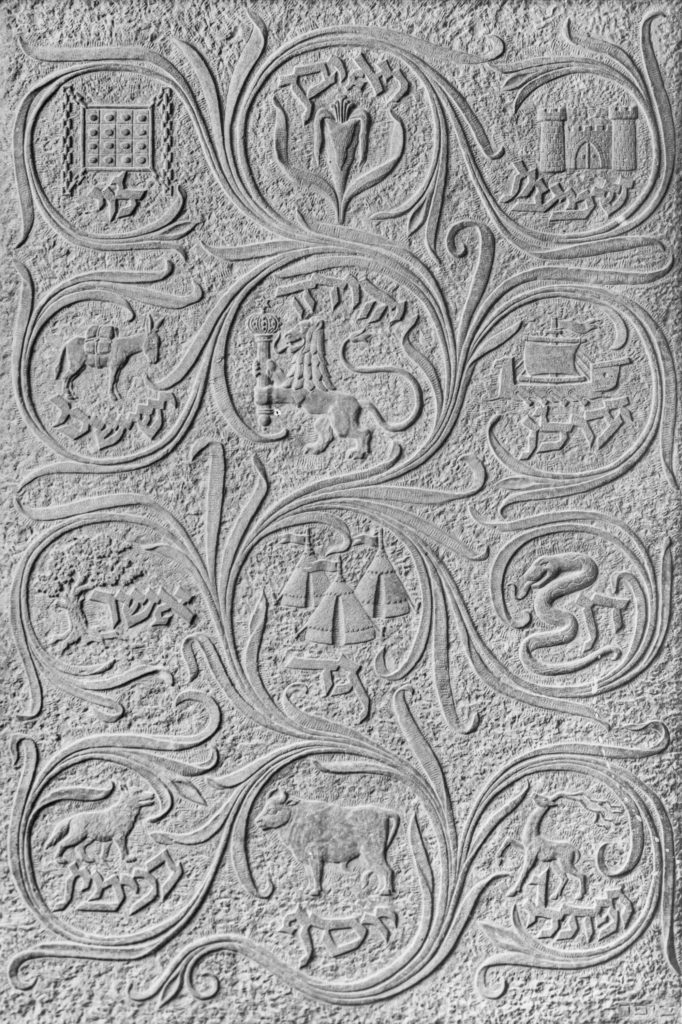

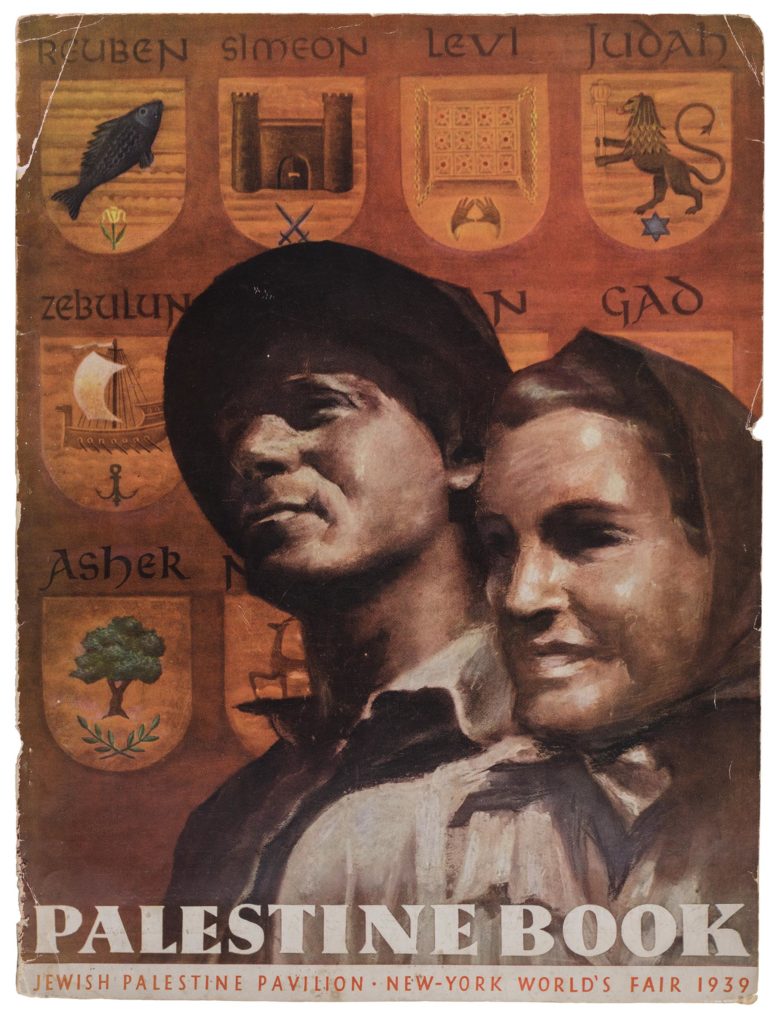

A large panel of the twelve tribes of Israel, signed by and attributed to Moshe Ziffer, stands out in contrast. A photograph of it, probably taken by Israel Zafrir, was among Ismar David’s papers. Although carved in stone, the ornamental scrollwork and the particular quality of the Sephardic lettering are characteristic of David’s work at the time. Indeed, the symbols are very similar to those on The Palestine Book, produced for the Palestine Pavilion in 1939.

None of these details resemble the work, up to that point or later, of Moshe Ziffer and it seems likely that a collaboration of some kind took place. Quite a lot of the work David produced in Jerusalem was executed by others: sign painters and other craftsmen for exhibitions or commercial signage—the carved wooden cover of the Jewish National Fund’s eighth Golden Book is another example—and he must have been accustomed to other people interpreting his designs. The staff of the Sieff Institute gave this gypsum panel to Chaim Weizmann on the eve of his inauguration as the President of Israel3As described on the Weizmann Institute web site: The Collection, Weizmann Wonder Wander in 1949. The Israel Museum dates it, however, as 1940/41. Today, it remains installed on a wall of Weizmann’s home in Rehovot. The design has enjoyed a much wider audience, though, if in ever decreasing size and quality, in many smaller metallic iterations.