Felix David, 1909–1938, brother.

The reseach of Doris Neu, on behalf of Stuttgart’s Stolpersteininitiative Fildervororte, pointed the way to Olaf Wittenberg’s perceptive article, “Drittes Reich: Ausgezeichnete Lebensrettung durch einen Juden” in Militaria, 29. Jahrgang, Heft 5, September/Oktober 2006, which in turn opened the door to this further research.

The tragedy of Felix David is one that we will never fully understand. He was certainly aware of the urgency of his family’s situation—he taught at schools that explicitly prepared students for new lives abroad. He had, for years, been an active participant in the Zionist youth movement, yet given the opportunity to leave Germany to join family in Palestine, he did not go. Felix was gifted and, we may suppose, ambitious. He wrote articles, gave lectures and participated in civic organizations. He was a responsible educator, who showed courage and quick-wittedness when he saved the life of a drowning woman. Why a young man of 29, two days after the pogrom of November 1938, simply gave up, not only on his own account, but on that of his wife and two very young sons, remains an enigma. Our only witness in Stuttgart at the time was shocked and appalled. Today we can hardly do more than speculate and assemble a virtual scrapbook of his press clippings and the cold police report of his family’s demise.

Childhood and Youth

Felix David was born on February 15, 1909 in Breslau, the first of three children, to Benzion Wolff David, an insurance agent, and Rosa Freund David, a teacher. His mother’s family was prosperous and prominent. Uncle Benno owned a stocking factory and was a member of the Kultuskommission I, one of two administrative bodies within Breslau’s Jewish community. Uncle Ismar was a jurist and author, member of the board of the Berlin Jewish Community and a co-founder of Prussian State Association of Jewish Communities; Uncle Samuel, a prominent rabbi in Hannover. Family history tells us that Felix was good-looking and “an absolute mathematical genius.”1According to niece Hannah Wende. He excelled in König Wilhelm Gymnasium, the alma mater of physicist and mathematician Max Born, who graduated in 1901. (The secular school was generally known for its equitable treatment of Jewish students.)2Garz, Detlef & Gesine Janssen p. 35 Über den Mangel an Charakter des deutschen Volkes. In the normal course of events, we may expect that he graduated in 1927 and must have then gone on to an institution of higher learning, but we don’t, as yet, know where.

1930

On March 16, 1930, the Jewish community in Breslau dedicated a new youth home, of which it was justifiably proud. The project had been a challenging undertaking, but the result was a modern, light-filled building with library, assembly room, darkroom, club rooms, central heating and garden plus living accommodations for eleven youths on the third floor. The young manager of the facility, Felix David, had recently relocated from Cologne. In his own short address in Breslau’s community newspaper, Felix noted the success the center enjoyed right from the outset and that he was available for consultation on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. Various reports make it clear, however, that the “soul”3Breslauer Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt, April, 1930, Nr. 4, p.56. of the center was its director and founder, Paula Ollendorff, teacher, social activist and first woman in Germany to become a town councilor. During his time at the youth home, Felix held meetings of the National Jewish Youth Circle (1) (2) and supported the Keren Kayemet Le-Israel, the Jewish National Fund, giving 6 DM himself. He was just 21 years old.

1931

In the February issue of the community newspaper, the synagogue board posted an announcement that it was looking for an unmarried manager for its youth home to begin on April 1. The Bar Kochba Sports Club addressed what the Jüdische Zeitung für Ostdeutschland called the “David case” in its general meeting on February 25 and the assembly unanimously passed a resolution protesting Felix David’s dismissal. They noted that the synagogue board has fired him although he had won the trust of the youth at the home and although the committe responsible for his position had refused to approve his removal. The resolution went on to commend Felix’s merits and his ability to build an uplifting educational program from the many poliltical-philosophical streams of Jewish youth groups.

Felix soldiered on. On Sunday evening, February 14, in a meeting of the National Jewish Youth Ring, he gave a talk on the topic: “Zionism and Messianism.” On March 23, despite a boycott by a few groups on the left, more than sixty youths gathered to hear a talk by a proponent of Revisionist Zionism (a more right wing movement, seeking to revise Herzl’s practical Zionism, by focussing on statehood). Felix was there representing the German Misrachi (orthodox religious) Zionist point of view, but he was also described as a “friend of Poale Zionism” (Marxist socialist Zionism). Just as he had done at the youth home, he demonstrated his ability to work with competing Zionist ideologies. The speakers were well received and the evening ended at 1 in the morning with applause for all involved. During a youth semimar from April 11-19, Felix delivered an address on “The Non-Zionistic Solutions to the Jewish Question.”

1932-33

Notwithstanding the unexplained action of the Breslau community board, the Ollendorffs must have liked what they saw, because Felix led classes, alongside Paula Ollendorff’s son, Fritz, at the newly-founded Jewish Youth School in Cologne, slated to open in October 1932. The leadership at the school sought to provide Jewish students with the “language, literature and history” that was their inheritance and to keep costs affordable for anyone who wanted to attend. Felix’s classes included: “Introduction to the Culture of Ancient Israel, illustrated by selection from the Book of Judges” and “The Genesis of Christianity (with regard to Modern Liturature).” He may also have been the housemaster of the school.

1934

In 1934, Felix was a probationary teacher in Beuthen, now Bytom in Poland, a city with a large Jewish community, an imposing synagogue and a municipal Jewish primary school. On March 13, the local Zionist group hosted a presentation by senior teacher, Dr. Goldstein-Gleiwitz. She spoke movingly of the anguish of Jewish children having their skulls measured in biology classes, as well as suffering numerous other indignities and neglect in non-Jewish schools. Felix took part in the general discussion that followed, in which all participants agreed to the urgency of founding of a Jewish middle school in Beuthen.

Under the auspices of the Local Organization of Jewish Youth Associations, an audience of over 40 people heard Felix lecture on “The Philosophy of the Bible, Job and Koheleth” as well as on “Halevi’s Book of the Kuzari and Maimonides’ Guide For the Perplexed.” When a performance of Jakobs Traum concluded the winter season of events for the organization, Felix introduced the work and praised the participating groups, who had come together to present an affirmatively Jewish work, selected to express a sense of Jewish history and the comfort it could provide.

1935-36

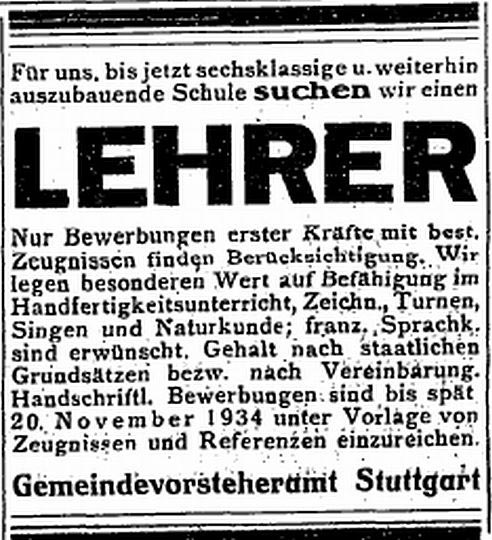

The Stuttgart Jewish School had been founded in March of 1934, with its new school building dedicated the following year on April 17. Architects Oskar Bloch and Ernst Guggenheimer managed, within a constrained budget and under difficult political circumstances, to erect a modern and modest (in keeping with the necessity to keep a low profile) edifice. The community rejoiced in having a relatively safe haven for their children and teachers made every effort to create an environment that was free of the existential anxiety then present in every Jewish home.4Zelzer, Maria p. 176 Weg und Schicksal der Stuttgarter Juden. Ein Gedenkbuch, 1964. The school administration was keenly aware of its responsibilities in response to National Socialist policies and stressed learning English, Spanish and modern Hebrew, as well as the general curriculum of Wurttemberg. The school, like Stuttgart’s Jüdisches Lehrhaus, taught manual skills, too, reflecting the conviction that intellect in a new culture was not marketable and one had better be prepared to work with one’s hands.

Exactly when Felix started teaching at the Jewish School in Stuttgart is a little nebulous. According to Maria Zelzer,5Zelzer, Maria p. 522 .ibid. Felix was a staff member in April 1935, however he gave a talk (“What Do the Current Times Demand of Jewish Parents?”) in Gleiwitz on January 26 and spoke at a week-long conference for leaders of Jewish youth groups there in July. (His topic was “How Do We Promote Jewish History in the [Youth] Leagues?,” in which he used Biblical examples and critically examined the books used to teach history.) At a cultural event on November 24, again in Gleiwitz, “Felix David, Beuthen” gave a talk entitled, “Our Current Situation and Nevertheless…Cultural Zionism” and the Judische Zeitung continued to identify him as probationary teacher, when on Feb 17, 1936, he gave a lecture, again for the Local Zionist Group. (The talk was on Leo Pinsker. Felix compared Pinsker’s ideology to Ahad Ha’am and Theodor Herzl and discussed the spiritual construction of Chibbath Zion philosophy and the concept of political Zionism.) The credit for his article, Suggestions on the Selection and Distribution of Materials in Jewish History Classes, appearing in the Jüdische Schulzeitung, June 1936, still placed him in Beuthen. (This article is a stark expression of Felix’s Zionism. He criticizes the handling of Jewish history in schools, which he sees as colored by a desire for assimilation and a rejection of the idea of a Jewish national culture. He posits that the Bible should not just be mined for religious fables for young children, but, more importantly, utilized for older children as a basis for history lessons and for instilling Palestine’s crucial place in Jewish life both in the past and the present.)

In any case, Felix was in Beuthen on August 30, 1935, when he married Ruth Rosenzweig. Ruth was born in Cologne on July 7, 1911, two years after her brother Kurt Ascher. Like Felix’s brother, Ismar, she had strabismus in one eye. She had attended a Protestant private school and a home economics school before she began a course in nursing, which she had been due to complete in the spring of 1934. However, in 1933, she emigrated to Palestine with her parents Siegmund and Martha, born Philippi, and presumably her brother. Ruth worked in a hospital as an unlicensed nurse until she left Palestine and returned to Germany in order to marry Felix David. According to her brother-in-law, she was completely dominated by her husband.

Although Felix’s name does not appear in the Stuttgart Telephone Book until 1937, a police report tells us he was certainly a teacher residing in Stuttgart, when he saved a woman from drowning (!) on June 23, 1936. As Felix told the police inspector:

I was at the public swimming area on June 23rd and happened to walk across from the stadium pool to the Neckar, just to check that none of our students was swimming in the river.

As I walked along the lower bank, I suddenly saw a woman in the water, awkwardly trying to swim on her back and apparently talking to herself. When, just then, she went under, I realized that the woman was drowning. I called to two rowers, who were lounging in their boat on the opposite bank, just in case, and went into the water. I swam to where the woman had gone under and just then come up again. As I came close to her, she tried to grab on to me. I pushed her away and shouted that she should turn on her back. I immediately succeeded in approaching her from behind and was able to pull her to the riverbank, using a rear rescue carry. In the meantime, the two rowers had arrived in their boat and helped me to carry the woman up the stairs.6Felix David in a report about the rescue. Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart (HstA S): Best. E 151/01, Bü 2830.

The Stuttgarter Neues Tagblatt cited the event on the same day7According to Der Schild, July 3, 1936. and, in the days that followed, a few Jewish newspapers picked up the story. (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)

Stuttgart seems to have been a perfect fit for Felix, who continued his involvement in Zionist groups and also taught at the Jewish Sports School. (He was a good swimmer and had taken life-saving courses during his student days.)8Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart (HstA S): Best. E 151/01, Bü 2830. In October, the Jüdischer Schulzeitung published a response to the article by Felix. Dr. Lotte Barschak in Berlin decried the orthodoxy of a purely Biblical and biographical Jewish history curriculum and advocated for one that showed the relationship between Jewish and non-Jewish culture. From December 9-11, 1936, he took part in two sports education courses at the othropaedic-gymnastic institute run by Alice Bloch (wife of architect Oscar Bloch).

1937

At the Regular General Meeting of Local Zionist Group on March 24, 1937, a new executive council was elected. As part of its supporting committee, Felix was responsible for culture and education. In the May issue of the community newspaper, he appealed to parents to send their children to community youth groups where crafts, reading, games and hiking, love of nature and a sense of community were offered. Felix outlined the advantages and necessity of organized youth groups in those dark times, when parents could hardly have the buoyancy of spirit to play with their children. He invited parents to meet the teachers and promised that children would not be indoctrinated politically in any way. He described the youthful optimism of the teachers and their desire to help children make their way in the Jewish world.

From June 17-20, Felix led Bible studies at a 3-day seminar of the Zionist District Association of Baden-Württemberg, held in Haigerloch, about 70 km away from his home and arranged the celebration after the Sabbath. At a school sporting event on July 28, he guided the small children with a sure hand.

A son, Benzion Wolf, was born to Ruth and Felix David on August 31.

In the October 16th meeting of the Friends of the Jewish School, Felix was elected to the school committee. The next day, he spoke at a farewell event for first chairman of the Hakoah Sports Club, Ernst Freudenheim. Around this time, too, Felix began teaching a course at the Lehrhaus about the report of the Royal Commission on Palestine, headed by Lord Peel. When he spoke to Local Zionist Group in Stuttgart about “Palestine’s Economy in Crisis—a report from a trip to Palestine” on November 1, it seems likely that he was referring to his own trip to Palestine, which his brother Ismar, who had been living in Jerusalem since 1932, recalled. The trip must have lent resonance to his talk at a showing of Weg in die Wirklichkeit, (The Path to Reality), as well as another film, Brit Hanoar, on November 24. Weg in die Wirklichkeit, by Ernst Mayer, dealt with the acheivements of a religious kibbutz in Eretz Israel and Felix received hearty applause for his enthusiastic description of the Bachad, an orthodox-Zionist-socialist youth movement and its synthesis of “[religious] law, work and Eretz Israel.” At the Hakoah Sports Club Hannukah party on December 4, he galvanized the audience with his words about the living symbol of the menorah and the fighting spirit of the Maccabees. For the Hanukkah festivities at school, Felix adapted the midrashic tale of the fox and the wolf for young students in a way both playful and inspiring. At a plenary meeting of the Jewish Directors Office, he gave a report about the continuation of the ninth class.

1938

Felix continued his involvement with the orthodox-Zionist youth movement. Zion, the monthly newsletter of the Central Office of Independent Misrachi National Organization of Germany, noted his appearances in connection with Weg in die Wirklichkeit. It seems probable that Felix used his own photos for the basis of a talk, “Atmospheric Pictures from a Trip to Palestine,” that Felix presented to the Women’s Association for Palestine Work on January 27, 1938. At a community meeting on February 2, Felix again spoke about changes to 9th class and the emphasis on preparation for emmigration. In Göppingen, he once more provided context for Weg in die Wirklichkeit and Brit Hanoar, discussing the current status of the Palestine question and the achievements and goals of the Misrachi. The films were well recieved by an audience in Heilbronn, too, where Felix spoke about the goals of the Misrachi. In late spring, the directors of the school held an evening lecture, entitled, “The Purpose of Hebrew in the Upbringing of a Jewish Child,” a topic initiated by the community newspaper. All the speakers recognized the social, moral and cultural value of teaching the Hebrew language in school. The only disagreement was its necessity in comparison with the normal curriculum. Felix took part in the discussion that followed.

The Davids’ second son, Yizchak Gideon, was born on June 11. Almost immediately, the elated parents placed an announcement in the Jüdische Rundschau.

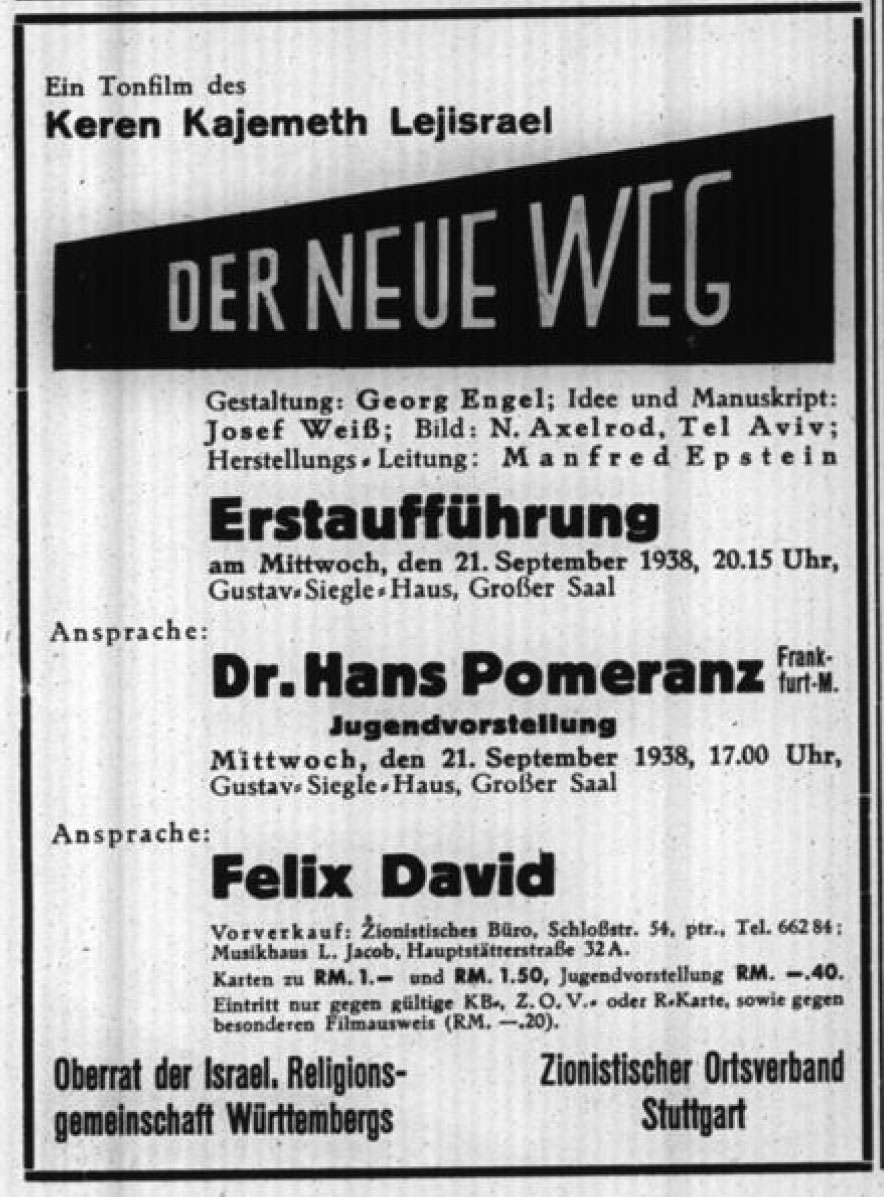

On September 21, Felix spoke to young people at an afternoon showing of the film Der Neue Weg (The New Path) from the Keren Kayemet, the Jewish National Fund, and thanked the speaker at the evening showing.

Felix was making 400 RM a year at the Jewish School plus an additional 50-75 RM from his teaching at the Sports School.9EA 99-001 Bü 164, Erhebungsbogen zur Dokumentation der Judenschicksale 1933-45, Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg. Despite the pleas of Ruth’s parents and the efforts of his brother, the couple had remained in Germany. What happened next, is almost unfathomable. Edith Goldschmidt, wife of the director of the Jewish School in Stuttgart and a teacher there herself, describes the events in her autobiography. On the day following the start of the pogrom, her husband had not returned home, as usual, for lunch.

Hours went by, until finally a younger colleague, Mr. David, who belonged to the orthodox community, came to me at about 4 o’clock. He told me what had happened that morning in the school. All the male teachers had been taken by the SS to a concentration camp. The camp was in Baden. He had not been in the school only by chance. Had I heard nothing about the synagogue and cemetery destruction? Now, he wanted to say goodbye.10Goldschmidt, Maria. Drei Leben: Autobiographie einer deutschen Jüdin, Stadt Steinfurt, 1992, 41.

Edith Goldschmidt goes on to write that female teachers had also been at the school and that most had already prepared to leave Germany.

The terror unleashed by the pogrom in the night of November 9 was apparently too much for Felix and Ruth to bear. Edith Goldsmith goes on to describe what happened after Felix left her.

I was so stunned from what I had just heard, that I just couldn’t really comprehend why he said goodbye so emphatically. His wife had had her second baby a month ago, and I knew that he had his travel permit for Australia in his pocket. Unfortunately, he had to leave me alone now, my colleague said to me, his wife was waiting for him. Everything looks worse than it is, one must not lose courage. Platitudes that he tried to use to hide what was really going on in his mind. He left. And two hours later, he and his wife and the two small children were found dead in their beds. He had poisoned his family and himself to escape the fate of the concentration camps—with a travel permit in his pocket. He was orthodox, observed all the religious laws down to the smallest detail, but his belief in God wasn’t enough to go from here to there. He was one of the most gifted mathematicians I have ever met. He could have saved himself and his family with a minimum of genuine piety, as we saved ourselves with God’s help, but in these hours of terrible fear and uncertainty, murder and suicide were easier than trusting in God.11Ibid., 41.

The police report states that Felix and his family were found in their apartment, dead from gas poisoning, at 8 a.m. on Saturday, November 12, two days after Edith Goldschmidt’s husband and others had been seized. (Emil Goldschmidt was released 14 days later.) Ms. Goldschmidt attended the services for the David family.

I went to the funeral of these first tragic victims of the demoralization, which now was growing rapidly. They were given an honorable burial in the Jewish Cemetery, but I will never forget the admonitory address the rabbi gave to his troubled congregation with regard to the dead.12Ibid., 41.

SOURCES

Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Goethe Universität, Frankfurt am Main: Der Israelit Frankfurt am Main; Jüdische Schulzeitung Mannheim; Gemeindeblatt der Israelitischen Gemeinde Frankfurt am Main; Zion: Monatsblätter für Lehre, Volk, Land Berlin; Gemeindeblatt der Israelitischen Religionsgemeinde zu Leipzig: Amtliches Nachrichtenblatt der Gemeindeverwaltung, Leipzig; Central-Verein-Yeitung: Blätter für Deutschtum und Judentum; C-V-Zeitung; Organ des Central-Vereins Deutscher Staatsbürger Jüdischen Glaubens, Berlin; Gemeinde-Zeitung für die Israelitischen Gemeinden Württembergs, Stuttgart; Der Israelit : ein Centralorgan für das Orthodoxe Judenthum, Mainz; Jüdische Rundschau : Allgemeine Jüdische Zeitung, Berlin; Jüdische Allgemeine Zeitung, Berlin; Mitteilungen des Reichsausschusses der Jüdischen Jugendverbände / Reichsausschuss der Jüdischen Jugendverbände; Der Schild,Berlin.

Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln DIgitale Sammlungen: Gemeindeblatt der Synagogen-Gemeinde zu Köln am Rhein

Das Digitale Forum Mittel- und Osteurop (DiFMOE) https://www.difmoe.eu/d/: Jüdische Zeitung, Breslau; Jüdische Zeitung für Ostdeutschland, Breslau

Archive.org: Breslauer Jüdisches Gemeindeblätt; Informationsblätter, Herausgebeben von der Reichvertretung der Juden in Deutschland

Archiv.org: Picard Collection: Gemeindeblatt des Landesverbandes israelitischer Religionsgemeinden Hessens