Stephen Sally Kayser, 1900–1988, art historian, curator, lecturer, teacher.

Stefan Salli Kayser was born in Karlsruhe where he studied art history, philosophy and musicology at the Technische Hochschule. He received his doctorate in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg in 1924. As editor and feature writer for the Mannheimer Zeitung and then, later writing for various newspapers in Berlin, he knew many of the luminaries in German visual arts and music through the beginning of the Nazi era. Kayser and his wife, painter Louise Darmstädter, left Germany for Czechoslovakia in 1935, where they spent three idyllic years before fleeing, with Kayser’s parents, to the Netherlands. From there, the family emigrated to the United States, living first in Cincinnati, then in New York and finally settling in southern California.

Kayser was an associate professor in the Department of Art at San Jose State College, when he was invited to help establish the Jewish Museum in New York. Accepting the position, Kasyer turned his polymathic knowledge of art, history, philosophy and culture, as well as a deep and sympathetic understanding of Jewish customs, to the museum’s mandate to “display and promote all forms of artistic expression in the Jewish tradition–painting, sculpture, architecture, music and letters.”1Jewish Telegraphic Agency Daily News Bulletin, May 5, 1947, p. 7. In partnership with Darmstädter, who had trained as a theatrical designer, Kayser sought to create ways to look at Jewish artifacts beyond the usual arrangement of an antique store.2 Stephen S. Kayser : Fluchtlinien / Interview von Sybil D. Hast, Berlin : VBB Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, 2016, p. 222. During his more than fifteen years at the Jewish Museum, Kayser curated over 80 exhibitions, showcasing both the museum’s vast historical collection and many contemporary artists, and oversaw the acquisition of important collections. He regretted the collapse of a plan for Marc Chagall to paint murals in the auditorium, which Kayser likened to an American Sistine Chapel. His other great disappointment was the removal of a long-neglected 18th century synagogue which Kayser himself had discovered in Vittoria Veneto and its re-installation on two floors inside the Jewish Museum.3 Stephen S. Kayser : Fluchtlinien / Interview von Sybil D. Hast, Berlin : VBB Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, 2016, p. 243. (This historical jewel, where incidentally Lorenzo da Ponte had been a bar mitzvah, eventually made its way to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.)

In 1962 he returned to southern California to join the faculty of the University of Judaism and direct the visual arts department of its School of Fine Arts. Kayser taught at the University of California at Los Angeles College of Fine Arts, much of the time involved in a program designed to integrate all art forms. It was a program for which this youthful pianist cum opera obsessive, erstwhile theater and music critic, who taught others how to identify medieval artists and could write about medieval art and modern music with equal erudition and engagement, was uniquely suited. He became a much loved and admired educator and spent many subsequent years teaching at UCLA Extension.

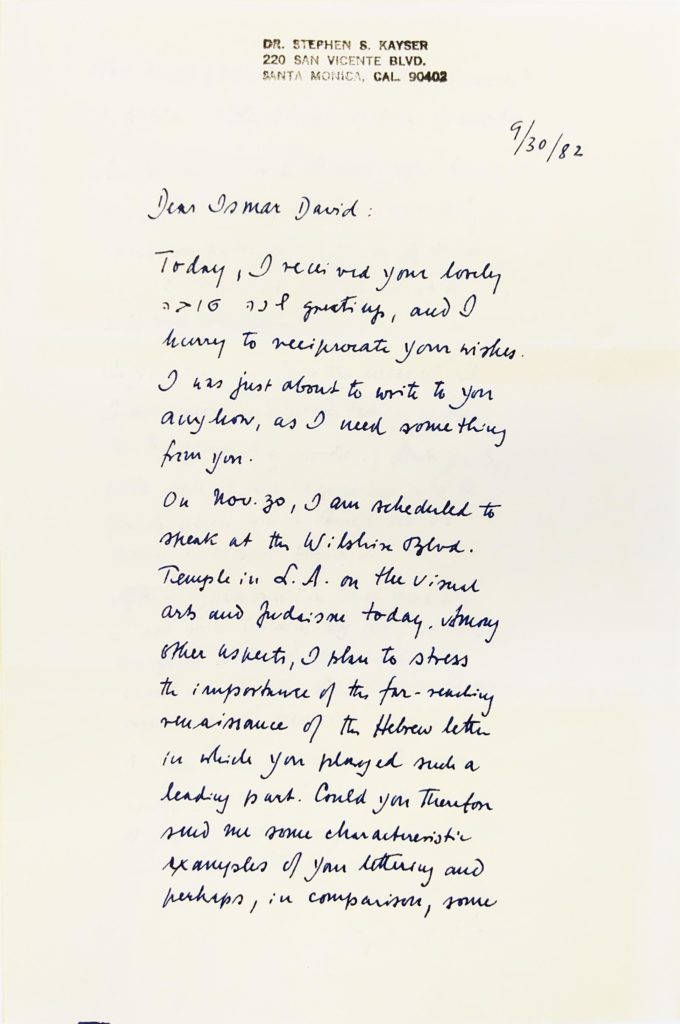

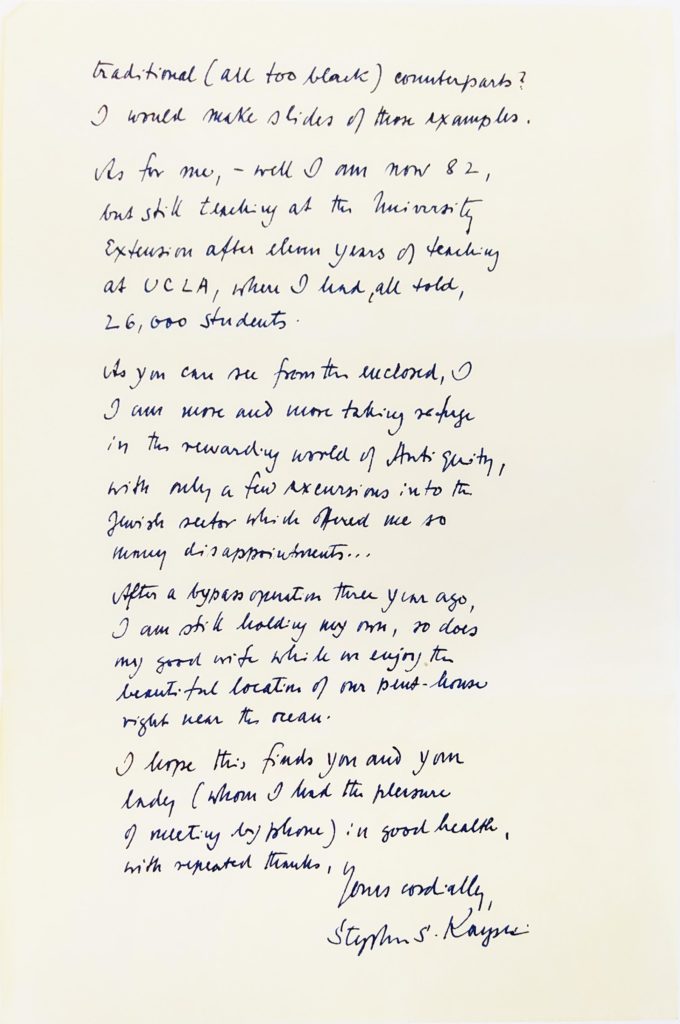

Stephen Kayser and Ismar David knew each other at least from the early 1950s, when the Jewish Museum mounted an exhibition of David’s work. In 1972, Kayser recommended that Erwin Jospe, Dean of Fine Arts at The University of Judaism, write to David about a possible exhibition. David’s response mentions his pleasure at hearing “…even if only indirectly, from Dr. Kayser for whom I have great fondness.” 4Letter from Ismar David to Erwin Jospe, September 25,1972, Ismar David papers, box 1, folder 5, Cary Graphic Arts Collection, RIT. On September 30, 1982, Kayser wrote a frank and cordial letter to David.

Dear Ismar David:

Today, I received your lovely שנה טובה greetings, and I hurry to reciprocate your wishes. I was just about to write to you anyhow, as I need something from you.

On Nov. 30, I am scheduled to speak at the Wilshire Blvd. Temple in L.A. on the Visual Arts and Judaism today. Among other aspects, I plan to stress the importance of the far-reaching renaissance of the Hebrew letter in which you played such a leading part. Could you therefor[e] send me some characteristic examples of your lettering and perhaps, in comparison, some traditional (all too black) counterparts? I would make slides of those examples.

As for me, –well I am now 82, but still teaching at the University Extension after eleven years of teaching at UCLA, where I had, all told, 26,000 students.

As you can see from the enclosed, I am more and more taking refuge in the rewarding world of Antiquity, with only a few excursions into the Jewish sector which offered me so many disappointments…

After a bypass operation three year[s] ago, I am still holding my own, so does my good wife while we enjoy the beautiful location of our pent-house right near the ocean.

I hope this finds you and your lady (whom I had the pleasure of meeting by phone) in good health, with repeated thanks,

Yours cordially

Stephen S. Kayser

In the spring of 1987, Sylvia D. Hast visited Dr. Kayser. At the conclusion of a series of interviews,5Interview of Stephen S. Kayser, University of California, Los Angeles Library, Center for Oral History Research. they they spoke about Existentialism and how Kayser personally came to terms with the vicissitudes of existence. Kayser said:

“This is a picture of life. However, Camus ends his book with ‘I am sure Sisyphus is a very happy man.’ That’s my philosophy. Pushing up that stone, coming down again, and be happy about it—not because of it, in spite of it.”