Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1908–1973, thirty-sixth president of the United States.

Lyndon Johnson will forever be reviled for escalating the war in Vietnam, but as far as domestic policy is concerned, he remains one of the most effective and progressive presidents in U.S. history. He used his immense political experience, forceful personality and commitment to social justice to support a sweeping vision for a more equitable nation. His War on Poverty helped lift millions of Americans above the poverty line. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial discrimination in public accommodations, interstate commerce, workplaces and housing. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 banned discriminatory practices that had disenfranchised voters in the southern states. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ended quotas based on ethnic origin. Johnson’s administration created Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, the Jobs Corps, VISTA, the National Endowment of the Arts and National Public Radio. Nevertheless, Johnson lost the New Hampshire primary in March 1968. Facing backlash for his social policies from the right and overwhelming opposition to the war from the left, as well as increasingly poor health, he ended his campaign for a second full term and retired to his ranch in Texas.

Johnson had been out of office for four months, when a short work of fiction by Paul Edward Gray appeared in the May 17th issue of New Yorker.1Gray, Paul Edward, “My Three Weeks at the White House.” New Yorker, 17 May 1969, pp. 32-33. It was a satirical swipe at trends in contemporary art and, rather gratuitously, the former president. Johnson’s Texas drawl is mocked and he appears as something of a Philistine, but, principally, it is his iconic initials that provide the necessary driver for the plot. In the story, the President personally calls an artist, acclaimed for having painted an “electric blue Bodoni” E “on a field of fuchsia”, and asks if he can paint all of the letters, specifically L, B and J. The artist installs himself in the “Situations room” for three weeks, creating various grandiose works on canvas of each letter, only to find out in the end that a monogram (for cufflinks, bathrobes, “and letter paper and saddles and speedboats”) was wanted. To cap it off, Eric F. Goldman’s unflattering memoir, The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson, which had appeared in January, gets a nod.

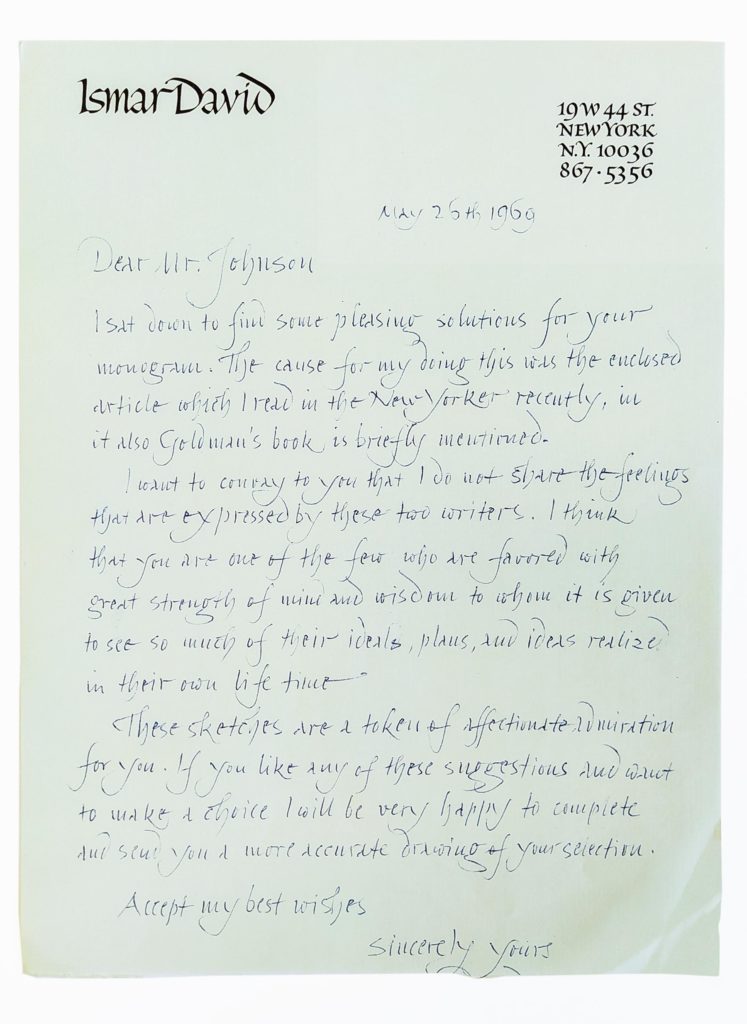

On May 26, 1969, Ismar David sent several designs to the former president, with a note.

Dear Mr. Johnson

I sat down to find some pleasing solutions for your monogram. The cause for my doing this was the enclosed article which I read in the New Yorker recently, in it also Goldman’s book is briefly mentioned.

I want to convey to you that I do not share the feelings that are expressed by these two writers. I think that you are one of the few who are favored with great strength of mind and wisdom to whom it is given to see so much of their ideals, plans, and ideas realized in their own lifetime.

These sketches are a token of affectionate admiration for you. If you like any of these suggestions and want to make a choice, I will be very happy to complete and send you a more accurate drawing of your selection.

Accept my best wishes

Sincerely yours

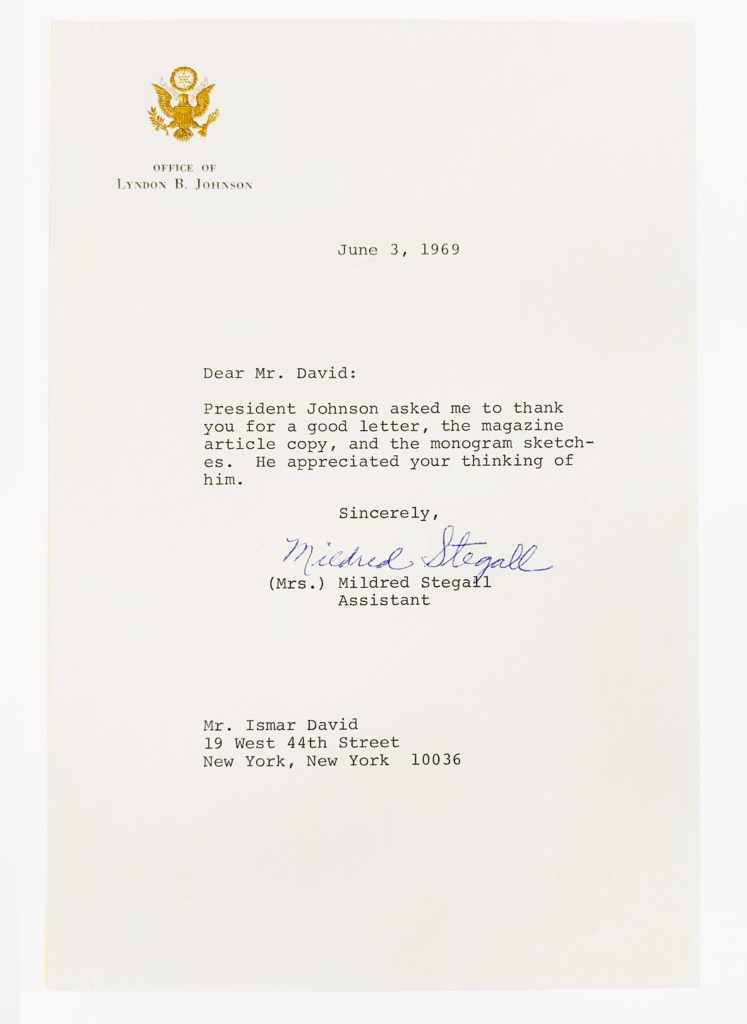

Johnson’s secretary responded on June 3.

Dear Mr. David:

President Johnson asked me to thank you for a good letter, the magazine article copy, and the monogram sketches. He appreciated your thinking of him.

(Mrs.) Mildred Stegall

Assistant