By Olaf Wittenberg

Published in Militaria, volume 29, issue 5, September/October 2006

Translated by Anuschka Tomat and Helen Brandshaft

As I researched how the state handles commendations for life-saving acts, one question kept coming up: How might National Socialist authorities have reacted to a rescue made by a person who was not of “German or kindred blood.”1Reichsbürgergesetz, §2 I. About the genesis and meaning of this term, cf. e.g., Andreas Rethmeier, “Nürnberger Rassengesetze” und Entrechtung der Juden im Zivilrecht, (Frankfurt a.M. u.a.: Lang, 1995), 151-155.

Because it’s hard to imagine that cases like this would ever have been reported to the responsible provincial ministry, I had very little hope of shedding light on this question with a concrete example. But while researching in the main state archive of Stuttgart, part of the provincial archive of Baden-Württemberg,2Provided no other source is given, all documents are from the Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart (HstA S): Best. E 151/01, Bü 2830. I actually came across exactly such a case.

The Rescue

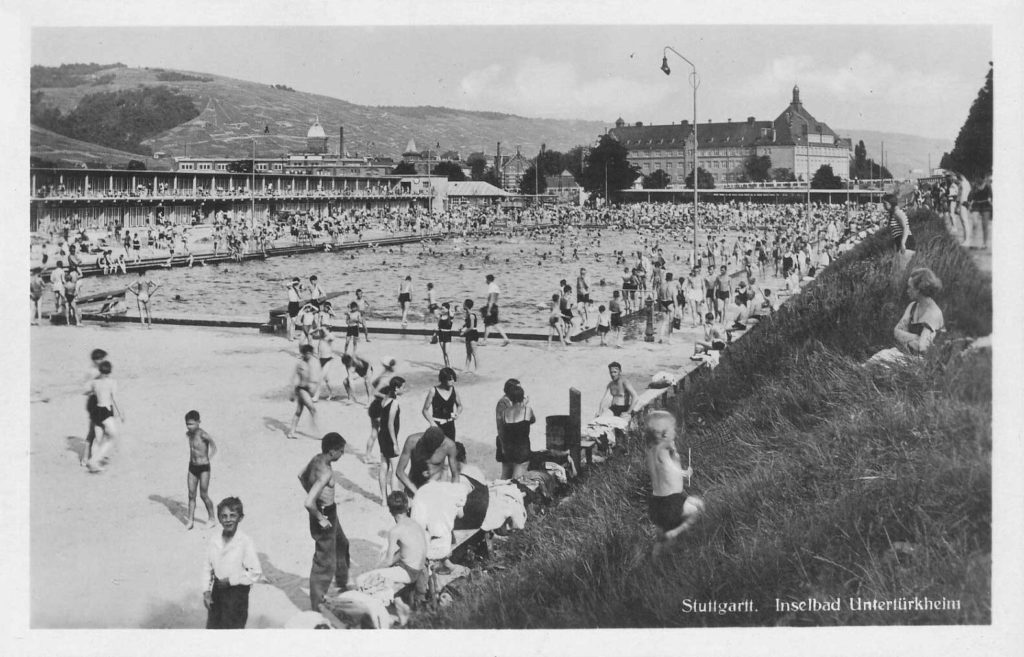

On June 23, 1936, the 27-year-old Felix David saved a 54-year-old woman from drowning in the Neckar River near the public pool in Stuttgart-Untertürkheim.

David gave his account of what happened:

As I walked along the lower bank, I suddenly saw a woman in the water, awkwardly trying to swim on her back and apparently talking to herself. When, just then, she went under, I realized that the woman was drowning. I called, just in case, to two rowers, who were lounging in their boat on the opposite bank and went into the water. I swam to where the woman had gone under and just then had come up again. As I came close to her, she tried to grab on to me. I pushed her away and shouted that she should turn on her back. I immediately succeeded in approaching her from behind and was able to pull her to the riverbank, using a rear rescue carry. In the meantime, the two rowers had arrived in their boat and helped me carry the woman up the stairs.3Felix David in a report about the rescue.

The investigation of the Stuttgart police about this accident, or rather, rescue case, describes the rescue and David’s efforts more clearly: “the rescue was made more difficult because he … could not bring Mrs. F directly to the shore, where the embankment was too smooth to land. He was forced to pull her to the nearest steps, which were 110 m away. The depth of the water at the site of the accident was about 2.5 m and was too deep to stand for the entire distance to the shore. The rowers arrived only in time to help get the victim up the stairs. After 45 minutes of resuscitation and with the help of oxygen, Mrs. F regained consciousness. Without the intervention of the teacher, Mr. David, she would surely have died.”4The Police Commissioner in Stuttgart writing to the Interior Minister of Württemberg on Oct. 3, 1936. (Az.:I 1211).

The Rescuer

Born in Breslau on February 15, 1909, the rescuer Felix David was 27 years old at the time of the rescue. He was Jewish, married and taught at the Jewish School in Stuttgart. While at college, he had taken part in life saving courses and was considered “a good swimmer.”5Cf.: The Police Commissioner in Stuttgart writing to the Interior Minister of Württemberg on Oct. 3, 1936. (Az.: I 1211).

The Conditions for Jews in Stuttgart at the Time of the Rescue

In June 1936, as Felix David carried out the rescue, Jews already suffered considerable discrimination, as a result of numerous laws and ordinances.6An—incomplete—overview is given, e.g., Hans-Jürgen Döscher, “Reichskristallnacht”: die Novemberpogrome 1938 (Frankfurt a.M. et al.: Ullstein, 1988), 15-21 and in tables, 180-184,. See also Anton Keim, ed., Tagebuch einer Jüdischen Gemeinde 1941/43, (Mainz: v. Hase & Koehler, 1968), 15-28. According to Keim, between 1933 and early summer 1935, there were already 70 laws and ordinances issued specifically for Jews, and by 1945, they totaled 431, disregarding regional specifics or severity. (Keim, Tagebuch, 16 and 19, referencing Bruno Blau, Das Ausnahmerecht für Juden in Deutschland 1933-1945. 2. ed. [Düsseldorf: Verlag Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland, 1954.]). About the situation in Württemberg and Stuttgart see, e.g., Roland Müller, Stuttgart zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (Stuttgart: Theiss, 1988) 281-309. In their commentary on the Nuremberg Laws of 1941, Loesener and Knost sketched the deteriorating circumstances since 1933, as follows:

The first step was to exclude people with alien blood from positions that govern or maintain the law, thus denying them public office or civil service positions.7See Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums. April 4, 1933 in German Government, Reichgesetzblatt, 1933, part I, 175. … That was followed by the elimination of Jews from state positions in public life, public health and German culture. The law to revoke the citizenship of naturalized Jews and to rescind the citizenship of German Jews, which was enacted on July 14, 19338RGBl, no. 35, April 8, 1933, part I, Berlin: Reichsverlagsamt, 1933. … segregated those interlopers who, with no innate right to belong to the German nation, had claimed citizenship, and those who, like criminals, had dragged the state to which they inherently belonged through the mud in front of the whole world. After restoring military sovereignty, the Wehrgesetz or Military Service Law enacted on May 21, 19359RGBl, part I, 1933, 378. … stipulated that only those with German blood could serve in the Armed Forces. The same principle formed the basis of the law regarding the state labor service, enacted on June 26, 193510RGBl, part I, 1935, 769. …However, legislation affirming the principle that only fellow Germans are allowed to influence policy making in the Reich had not yet been passed.11B. Lösener and F. A. Knost, Die Nürnberger Gesetze: Mit den Durchführungsverordnungen und den sonstigen einschlägigen Vorschriften, 4th ed. (Berlin: Vahlen, 1941), 11.

Among other things, this regulation was incorporated in the “Nuremberg Laws”12About the laws and by-laws, see Lösener et al., Die Nürnberger Gesetze. About antecedents, see, e.g., Cornelia Essner, Die “Nürnberger Gesetze” oder die Verwaltung des Rassenwahns 1933-1945, (Paderborn et al.: Schöning, 2002), especially 76-112; about the effects, e.g., Essner, Die “Nürnberger Gesetze”; Andreas Rethmeier, “Nürnberger Rassengesetze” und Entrechtung der Juden im Zivilrecht in Rechtshistorische Reihe, H.-J. Becker, Brauneder, W.; Caroni, P. et.al., eds., vol. 126. (Frankfurt a.M. u.a.: Lang, 1995), especially 291-386. The “Nuremberg Laws” were lifted with Allied Control Council Law No. 1, Article 1, ¶ 1 g (Blutschutzgesetz) and j (Reichsbürgergesetz) in Military Government Gazette, Germany, 21st Army Group Area of Control, no. 3, 1. that were introduced at the “Party Rally of Freedom” held on September 15, 1935. The Reich Citizenship Law13RGBl, part I, 1935, 1146. See also Erste Verordnung zum Reichsbürgergesetz (VOzRBürgG) in RGBl, 1935, part I, 1333; ibid., 1524; ibid., 1938, 627; ibid., 969; ibid, 1403; ibid., 1545; ibid., 1751; ibid., 1939, 47; ibid., 891; ibid., 1097; ibid., 1940, 872; ibid., 1941, 722; ibid., 1943, 268; ibid., 372. The first ten regulation in VOzRBürgG, along with further implementation provisions, printed with commentary in Lösener et al., Die Nürnberger Gesetze, 28-30 and 36-114; all legislative texts in Rethmeier, “Nürnberger Rassengesetze,” 414-439. established that “a Reich citizen … [is] only that subject of the state who is of German or related blood, and proves by his conduct that he is willing and fit to faithfully serve the German people and Reich…The Reich citizen is the sole bearer of full political rights in accordance with the law.”14RbürgG, § 2 I, III. According to the then prevalent view(!), this led directly to the conclusion: “A Jew cannot be a citizen of the Reich. He cannot exercise the right to vote. He cannot hold public office.”151. VOzRBürgG, § 4 I. In RGBl, 1935, part I, 1333.

Rethmeier emphasizes that the Nuremberg Laws, which were comprised of two separate laws: The Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor played16RGBl, 1935, part I, 1146f. See also the implementation orders in RGBl, 1935, part I, 1334; ibid., 1940, 394; ibid., 1941, 384. The first two ErgVOzBlSchG, printed with commentary in Lösener et al., Die Nürnberger Gesetze, 30-31 and 114-140; all legislative texts in Rethmeier, “Nürnberger Rassengesetze,” 440-44.

…a more important role than could immediately be recognized. Not only did the laws embody the Nazi racial ideology, but they also represented the crucial legal step in transforming this ideology into policy and implementing it. These measures were also crucial in the subsequent further disenfranchisement of Jews, which in the end led to the legal justification for genocide.17Rethmeier “Nürnberger Rassengesetze,” see above.

From today’s perspective, the Nuremberg Laws were … an essential aspect of what is known as ‘The Final Solution’. They laid the comprehensive foundation for a rationally constructed system that helped justify the systemic disenfranchisement of Jews that continued to be perfected leading up to the ‘Final Solution’.18Rethmeier, “Nürnberger Rassengesetze,” 387, cf. Uwe Dietrich Adam, Judenpolitik im Dritten Reich, in Tübinger Schriften zur Sozial- und Zeitgeschichte, vol. 1. (Düsseldorf: Droste, 1972.)

The Official Acknowledgment of the Rescue

In order to decide which official commendation should properly acknowledge Felix David’s life-saving act, an assessment of the danger involved, among other things, was necessary. To this end, the Stuttgart Police Commissioner’s report to the Württemberg Interior Minister, dated October 3, 1936, stated:

David is a good swimmer, who during his studies also attended life saving courses. Under these circumstances, the risk to his own life was neither especially high nor high, so awarding the Life-Saving or Commemorative Medal doesn’t come into consideration.19Cf. Verleihung der Rettungsmedaille und der Erinnerungsmedaille für Rettung aus Gefahr des Deutschen Reiches, RGBL, 1933 part I, no. 35; ibid., part I, no. 71; Württemberg, Regierungsblatt für Württemberg, 1934, no.2, § 2, (Stuttgart: 1934)12. Still, there was a risk to his life, even if a more diminished one, because of the great distance to the shore and the attempt of the victim to grab onto him, and the rescue should be appreciated as a courageous act at the risk of his own life. David deserves an award. I propose that he be publicly commended. In doing so, I assume that the circumstance that David is Jewish should present no barriers as to the kind of award given, because, in this case, it concerns the rescue of a human life, and by a Jew, from whom one would not readily expect an act of courage.20The Police Commissioner in Stuttgart on October 3, 1936, writing to the Württ. Interior Minister (Az.: I 1211).

Whether the assessment in the last sentence that this rescue was “by a Jew, from whom one would not readily expect an act of courage” was merely the opinion “demanded” by society or also the personal opinion of the writer, cannot be determined on the basis of these records. The simultaneously expressed expectation “that the circumstance that David is Jewish should present no barriers as to the kind of award given” could indeed indicate a certain contradiction of the opinion that society “demanded.”

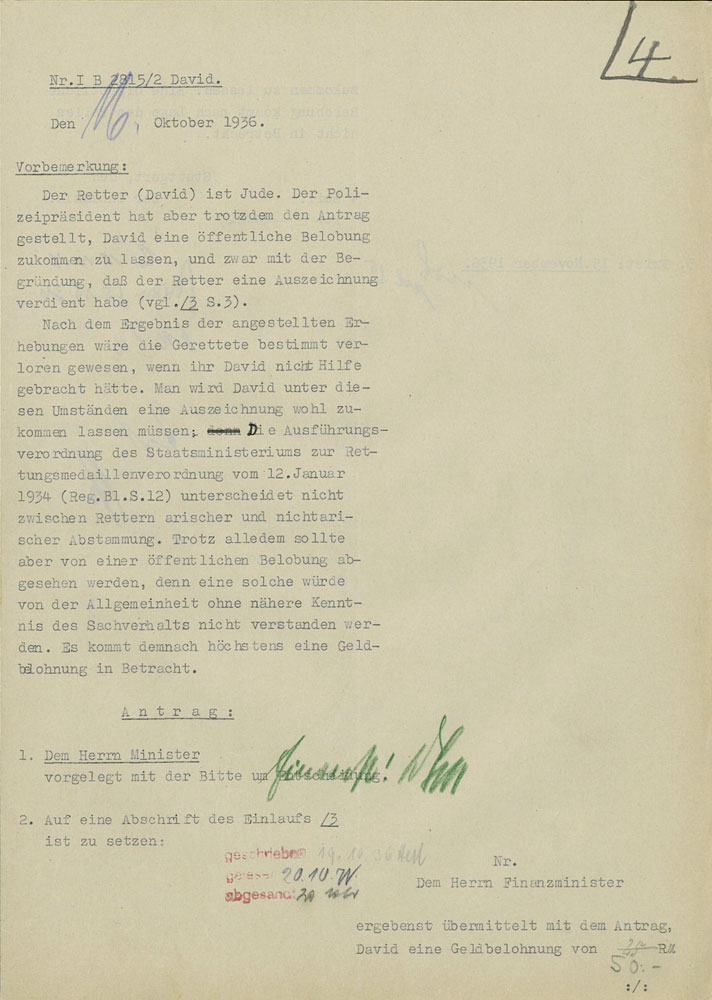

The Württemberg Interior Ministry, which was in charge of granting rewards and writing acknowledgments,21Württemberg, Regierungsblatt, 1934. See also Reichs Minister of the Interior Frick on April 26, 1933, writing to the Reich Governor and the state governments (Az.: I B 1737/14.4). (HStS S.: Best. E 130 b, Bü. 22, Bl. 184). determined:

The rescuer (David) is a Jew. The Police Commissioner has nevertheless proposed that David be given a public commendation, and indeed on the grounds that the rescuer deserves an award … According to the findings of the civil inquiry, the victim would surely have died, if David had not come to her assistance. Under these circumstances, David will likely have to be given a commendation. The [Württemberger] Ministry Framework for Commendations, from January 12, 1934 … does not distinguish between Arian and non-Arian rescuers. Despite all that, a public commendation should be denied, because the general public would not understand such an award without having more details about the situation. A monetary reward is the most that should be considered.22Württ. Interior Department in a request from October 16, 1936 (Az.: I B 2815/2).

In fact, a monetary reward was requested from the Ministry of Finance and was granted. An interesting detail here is that the “usual” amount of 25 RM was initially entered on the application, but someone—who cannot be identified—crossed it out and replaced it with 50 RM. This amount corresponds to the reward granted for a rescue at the risk of the life of the rescuer, if the state does not confer a medal or if the rescuer preferred financial acknowledgment.

Seventy [now eighty-two] years ago, on October 31, 1936, the Württemberg Interior Ministry finally issued this official order to the Police Commissioner in Stuttgart:

Herewith, the Finance Minister has allotted a monetary reward of 50 RM to the teacher Felix David … for the life-saving rescue at the risk of his own life, that took place on June 23, 1936. The state treasury is directed to pay David the amount. He is to be informed accordingly. Because of the circumstances of the case, a public commendation does not come into consideration.23Württ. Interior Department on Oct. 31, 1936 in a decree to the Police Commissioner in Stuttgart (Az.: I B 2815/3). Emphasis in orginial.

The Further Life of the Rescuer

Finally, this raises the question, what happened to Felix David, a man who, during the terrible years under the National Socialists, was honored by the state for his heroic rescue. Here, the pogrom in November 1938—trivialized by the name Reichskristallnacht–assumes critical importance.

The Pogrom in November 1938

On October 27 and 28, 1938, twelve thousand men, mostly Jews with Polish citizenship were arrested and deported to a German-Polish no man’s land, where they remained trapped for several days in catastrophic conditions, until Poland took them in. This action by the National Socialist regime was in response to the Polish government’s decision on October 6, 1938 (made public on October 15, 1938) to require a special symbol in the passports of all Polish citizens who had been living outside of the country for more than 5 years. Otherwise, their Polish passports would become invalid as of October 30, 1938, taking away their Polish citizenship and, with it, the possibility of returning to Poland. So, the deportation, according to the contemporary point of view (!), should prevent Germany from “having 50,000 stateless, formerly Polish, Jews dropped in its lap, as a consequence of their expatriation.”24v. Weizäcker, according to Müller, Der Branddirektor als Brandstifter, 490.

Even the Grynszpan family, who lived in Hannover and had Polish-Jewish roots, found themselves among the deported. Their son, Herschel Feibel Grynszpan, who was living illegally in Paris, found out about the deportation of his family and their calamitous circumstances at the same time that the French regime denied the legalization of his stay in France. On November 7, 1938, he attempted to assassinate the Secretary of the Legation, Ernst vom Rath, in the German embassy. Two days later, vom Rath succumbed to severe gunshot wounds.25Cf. e.g., Döscher, “Reichskristallnacht,” 57-67; Müller, Der Branddirektor als Brandstifter.

In response to the assassination, Pogrom-like attacks against Jewish businesses and synagogues occurred in some cities as soon as the nights of November 8 and 9, 1938. Joseph Goebbels spoke at a memorial celebration in Munich honoring Hitler’s 1923 attempt to overthrow the government. His implicit exhortation26For the significance of November 9th, see, e.g., Jürgen Genuneit, Blutfahne und Totenkult (Stuttgart: Stuttgart Kulturamt, ed., 1984). to high-ranking National Socialists led to the events of the nights of November 9 -10, when

…in all parts of the German Reich from east Prussia to the Rhineland and from Schleswig-Holstein to the Tirol, … almost all synagogues were burned down, and most Jewish businesses and homes demolished as well… Before the fires were set, many places saw desecration of synagogues and abuse of individual Jewish community members. … During the course of the pogrom, many Jews, regardless of age or gender, were beaten, derided, humiliated or killed.27Döscher, “Reichskristallnacht,” 80. cf. ibid., 77-108.

The Situation in Württemberg and Stuttgart

On November 12, 1938, the American Consul General in Stuttgart, Samuel W. Honaker, informed the American Ambassador in Berlin, Hugo R. Wilson,

…that the Jews of Southwest Germany have suffered vicissitudes during the last three days which would seem unreal to one living in an enlightened country during the twentieth century if one had not actually been a witness of their dreadful experiences, or if one had not had them corroborated by more than one person of undoubted integrity. To the anguish of mind to which the Jews of this consular district have been subjected for some time, and which suddenly became accentuated on the morning and afternoon of the tenth of November, were added the horror of midnight arrests, of hurried departures in a half-dressed state from their homes in the company of police officers, of the wailing of wives and children suddenly left behind, of imprisonment in crowded cells, and the panic of fellow prisoners. … So great had become the panic of the Jewish people in the meantime that … Jews from all sections of Germany thronged into the [Stuttgart Consulate’s] office, …begging for an immediate visa or some kind of letter in regard to immigration which might influence the police not to arrest or molest them. … Jewish fathers and mothers with children in their arms were afraid to return to their homes without some document denoting their intention to immigrate at an early date. … Practically all the Jewish shops in the Stuttgart consular district are reported to have been attacked, ransacked, and devastated. … Most of the Jewish shops in Stuttgart are situated in the main business section of the city. On the Königsstrasse, the principal business street, no looting was observed, but in the side streets looting was noticed in a number of cases. …It has been learned from reliable sources that practically the entire male Jewish population of the city of Stuttgart, ranging from the age of eighteen to sixty-five years, has been arrested by authorities representing the police. … During the course of November 11th some of the persons arrested were transported to Welzheim, which is the most important concentration camp in Württemberg. Arrests were also made as late as 10 A.M. on Saturday, the 12th of November. … Many Jewish men, some of whom are of excellent business standing, are reported to have left their homes on Thursday [November 10, 1938] and to have disappeared in the meantime. Their friends assume that they are wandering about, in the hope that possibly the storm will blow itself out and they will be left unmolested. … Particularly among older Jews, there are naturally rumors about a lot of suicides that have so far remained unconfirmed. Although the writer has spoken with the proprietors of homes which have been demolished in other parts of Germany during the last few days, no attacks on private houses and apartments occupied by Jews in Württemberg have been reported, … with the exception of two isolated instances. … After a period of three days during which persecutive measures against the Jews have been unprecedented in this part of Germany, depression among this section of the population has become indescribable. Many Jewish women are afraid that the worst is yet to be experienced. They look forward with dread to the day on which Herr von Roth [sic]will be buried.28The American General Consul S. W. Honaker on Nov. 12, 1938 in a confidential letter to the American ambassador H.R. Wilson in Berlin. Printed in Stuttgart, Kulturamt, ed., 1984, 508-510. Extract in Thalmann R. et al., 1987, 99. See also Müller, Der Branddirektor als Brandstifter, as well as the eyewitness accounts in Maria Zelzer, Weg und Schicksal der Stuttgarter Juden. Ein Gedenkbuch herausgegeben von der Stadt Stuttgart (Stuttgart: Klett, 1964), 196-202. English language source: German History in Documents and Images, vol. 7. Nazi Germany, 1933-1945. American Consul Samuel Honaker’s Description of Anti-Semitic Persecution and Kristallnacht and its Aftereffects in the Stuttgart Region (November 12 and November 15, 1938), url: http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/pdf/eng/English_33.pdf, accessed April 19, 2019.

During these riots, the workplace of Felix David, the Jewish School near the devastated Stuttgart Synagogue, remained spared, although its furniture was indeed looted and the building immediately seized by the National Socialists. Only later, after tough negotiations, was it given back.29Cf. Müller, Der Branddirektor als Brandstifter, 503; Müller, Stuttgart zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, 307; about the creation of the Jewish school in Stuttgart in April 1934, see ibid., 289.

The Death of the David Family

In the wake of the deadly violence and waves of arrests, the married couple, Felix and Ruth David committed suicide with their two children (Benjamin Wolff, born in August 1936 and Gideon Isaak , born in June 1938) on November 12, 1938. The man who the state had “secretly” commended for saving a life had been driven to his death by that same state only two years later.

The grave of the family can be found in the Jewish section of the Prague Cemetery in Stuttgart.30Personal note from Ms. E. Warscher in the Genealogy Office of the Jewish Community Württemberg in Stuttgart to the author on Feb. 22, 2006. In my research, I found indications in Paul Sauer, Die Schicksale der jüdischen Bürger Baden-Württembergs während der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgungszeit 1933-45 (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1969), 370-371; R. Thalmann and E. Feinermann, Die Kristallnacht (Frankfurt a.M: Jüdischer Verlag bei Athenäum, 1987), 100; Zelzer, Weg und Schicksal, 196. The David family is named in the commemorative book published by the directors of the Stuttgart archive on 407 und 461 (Rosenzweig, married name David, Ruth). Sauer cites, for the period between 1933 and 1945, a total of 165 confirmed suicides among the approx. 32,000 Jewish citizens, who resided prior to Jan. 30, 1933 in today’s Baden-Württemberg, 61 of which in 1938 and 1939. Sauer considers it indeed “very likely, that the number of [actual] suicides is substantially higher than 165.” (Sauer, Die Schicksale der jüdischen Bürger Baden-Württembergs, 265). For further suicides directly connected to the November pogroms, Sauer cites one case each in Heidelberg, Karlsruhe and Stuttgart, as well as two cases in Mannheim (ibid., 266). Thalmann et al., Die Kristallnacht, mention cases in Berlin (92), Hilden (110) and Nürnberg (98).

The translators wish to thank Olaf Wittenberg for his kind permission to reproduce this article. Mr. Wittenberg informs us that, despite his extensive research into the subject, Felix David’s bravery on June 23, 1938 remains the only known example of the National Socialist authorities having honored a Jewish person for saving a life.31Olaf Wittenberg in an email to Anuschka Tomat on April 17, 2019.